Thomas Coens Published in ‘The Conversation’

Why Franklin, Washington and Lincoln considered American democracy an ‘experiment’ – and were unsure if it would survive

From the time of the founding era to the present day, one of the more common things said about American democracy is that it is an “experiment.”

Most people can readily intuit what the term is meant to convey, but it is still a phrase that is bandied about more often than it is explained or analyzed.

Is American democracy an “experiment” in the bubbling-beakers-in-a-laboratory sense of the word? If so, what is the experiment attempting to prove, and how will we know if and when it has succeeded?

Establishing, then keeping, the republic

To the extent you can generalize about such a diverse group, the founders meant two things, I would argue, by calling self-government an “experiment.”

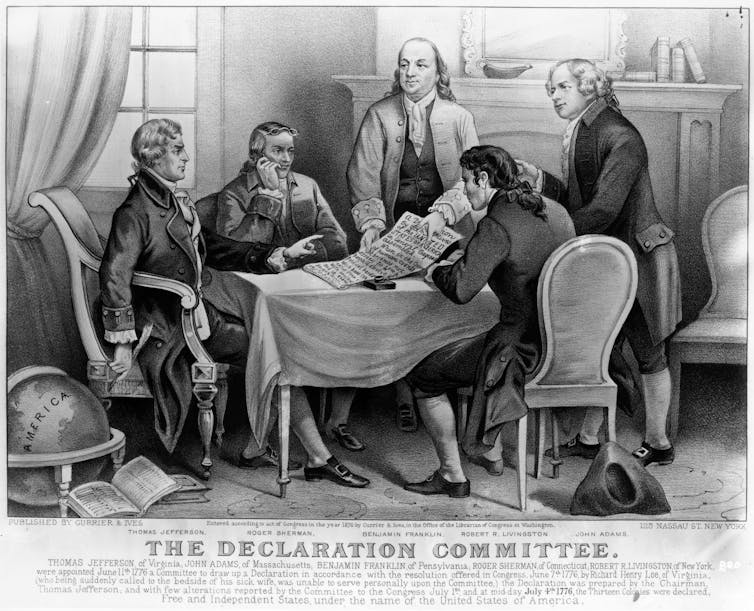

First, they saw their work as an experimental attempt to apply principles derived from science and the study of history to the management of political relations. As the founder John Jay explained to a New York grand jury in 1777, Americans, acting under “the guidance of reason and experience,” were among “the first people whom heaven has favored with an opportunity of deliberating upon, and choosing the forms of government under which they should live.”

Alongside this optimistic, Enlightenment-inspired understanding of the democratic experiment, however, was another that was decidedly more pessimistic.

Their work, the founders believed, was also an experiment because, as everyone who had read their Aristotle and Cicero and studied ancient history knew, republics – in which political power rests with the people and their representatives – and democracies were historically rare and acutely susceptible to subversion. That subversion came both from within – from decadence, the sapping of public virtue and demagoguery – as well as from monarchies and other enemies abroad.

When asked whether the federal constitution of 1787 established a monarchy or a republic, Benjamin Franklin is famously said to have answered: “A republic, if you can keep it.” His point was that establishing a republic on paper was easy and preserving it the hard part.

Optimism and pessimism

The term “experiment” does not appear in any of the nation’s founding documents, but it has nevertheless enjoyed a privileged place in public political rhetoric.

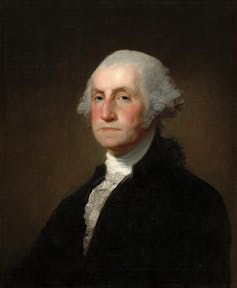

George Washington, in his first inaugural address, described the “republican model of government” as an “experiment entrusted to the hands of the American people.”

Gradually, presidents began to talk less of a democratic experiment whose success was still in doubt than about one whose viability had been proven by the passage of time.

Andrew Jackson, for one, in his 1837 farewell address felt justified in proclaiming, “Our Constitution is no longer a doubtful experiment, and at the end of nearly half a century we find that it has preserved unimpaired the liberties of the people.”

Such statements of guarded optimism about the American experiment’s accomplishments, however, existed alongside persistent expressions of concern about its health and prospects.

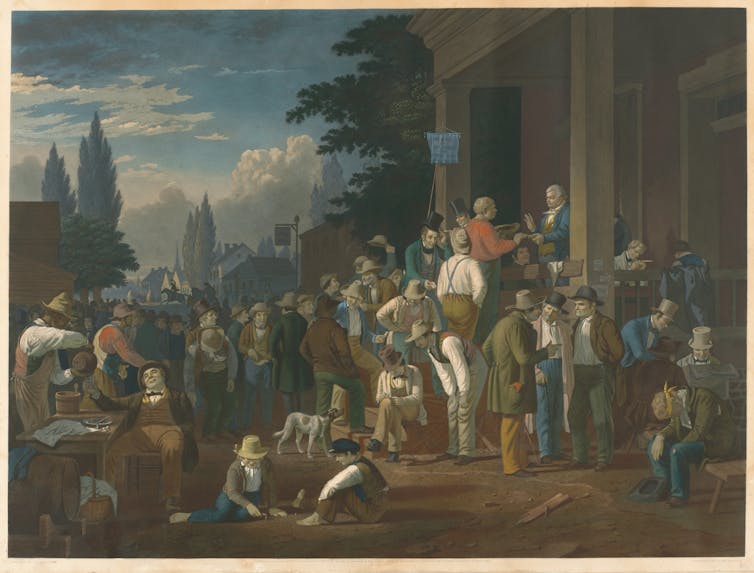

In the period before the Civil War, despite participating in what in hindsight was a healthy, two-party system, politicians were forever proclaiming the end of the republic and casting opponents as threats to democracy. Most of those fears can be written off as hyperbole or attempts to demonize rivals. Some, of course, were sparked by genuine challenges to democratic institutions.

The attempt of Southern states to dissolve the Union represented one such occasion. In a July 4, 1861, address to Congress, Abraham Lincoln quite rightly saw the crisis as a grave trial for the democratic experiment to survive.

“Our popular Government has often been called an experiment,” Lincoln observed. “Two points in it our people have already settled – the successful establishing and the successful administering of it. One still remains – its successful maintenance against a formidable internal attempt to overthrow it.”

Vigilance required

If you tried to quantify references to the democratic “experiment” throughout American history, you would find, I suspect, more pessimistic than optimistic invocations, more fears that the experiment is at imminent risk of failing than standpat complacency that it has succeeded.

Consider, for example, the popularity of such recent tomes as “How Democracies Die,” by political scientists Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt, and “Twilight of Democracy,” by journalist and historian Anne Applebaum. Why this persistence of pessimism? Historians of the United States have long noted the popularity since the time of the Puritans of so-called “Jeremiads” and “declension narratives” – or, to put it more colloquially, nostalgia for the good old days and the belief that society is going to hell in a handbasket.

The human-made nature of our institutions has always been a source of both hope and anxiety. Hope that America could break the shackles of old-world oppression and make the world anew; anxiety that the improvisational nature of democracy leaves it vulnerable to anarchy and subversion.

American democracy has faced genuine, sometimes existential threats. Though its attribution to Thomas Jefferson is apparently apocryphal, the adage that the price of liberty is eternal vigilance is justly celebrated.

The hard truth is that the “experiment” of American democracy will never be finished so long as the promise of equality and liberty for all remains anywhere unfulfilled.

The temptation to give in to despair or paranoia in the face of the experiment’s open-endedness is understandable. But fears about its fragility should be tempered with a recognition that democracy’s essential and demonstrated malleability – its capacity for adaptation, improvement and expanding inclusivity – can be and has historically been a source of strength and resilience as well as vulnerability.![]()

Thomas Coens, Research Associate Professor of History, University of Tennessee

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.