Bauer’s ‘Becoming Catawba’ Earns Best Ethnohistory Award

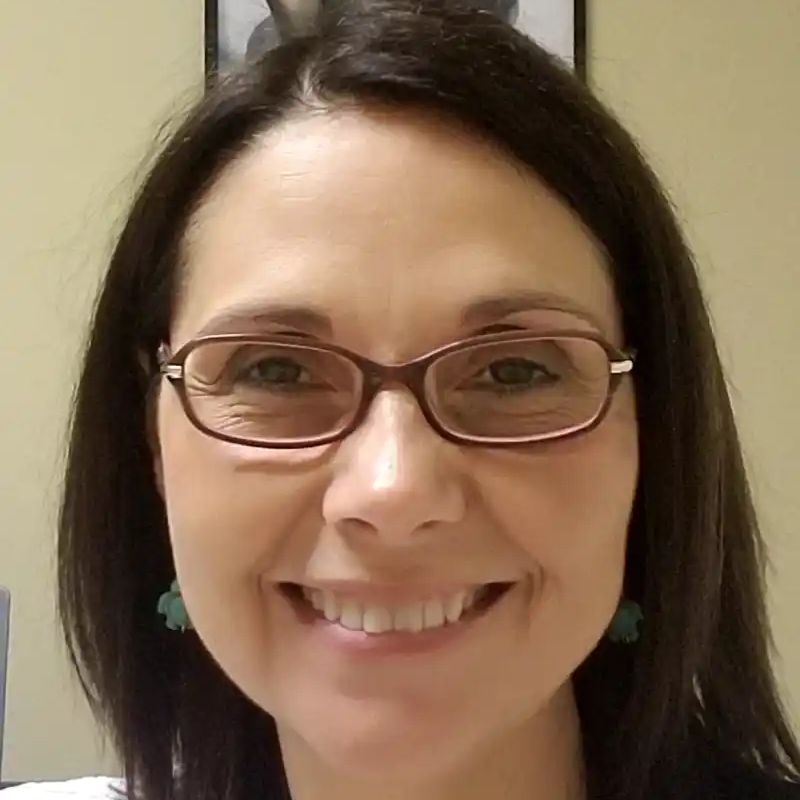

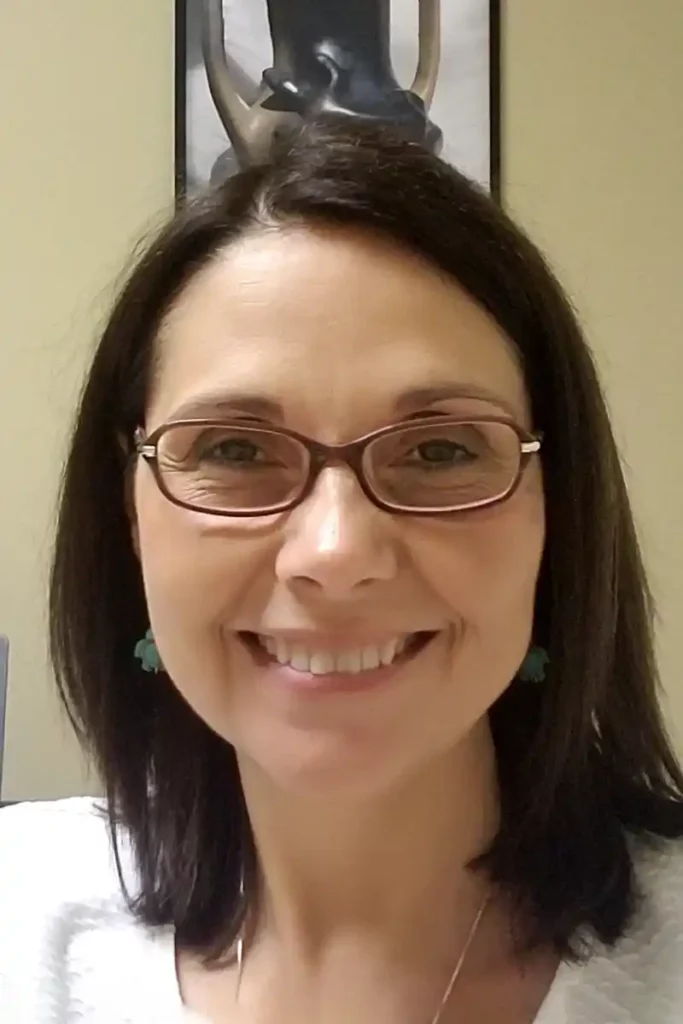

Brooke Bauer, assistant professor in the Department of History, received the 2023 Erminie Wheeler-Voegelin Book Award from the American Society for Ethnohistory (ASE) for her book, Becoming Catawba: Catawba Indian Women and Nation Building, 1540-1840 (2023).

The award recognizes the best book in the field of ethnohistory published in the last year. Bauer’s work investigates Catawba women as central characters in the history of the Catawba people, examining their vital roles as women, mothers, providers, and protectors to reveal how they created and maintained an identity for their people and helped build a nation.

In citing the book’s award-winning qualities, the ASE wrote, “Bauer constructs a riveting narrative about how the communities, economies, families, and polities of Catawbas in the Carolinas became intricately entwined and maintained over three centuries of turmoil brought about by European and US colonialism. In so doing, she crafts not only a powerful counter narrative to male-dominated stories of colonial diplomacy and warfare, but also a narrative of national creation and building rather than one of decline.”

ASE also noted Bauer’s careful research, interdisciplinary source-mining, and convincing arguments forged an “entirely engaging” story, writing, “Bauer shows how to combine family research with archaeological and documentary research with huge rewards for specialists and non-specialists alike.”

Bauer’s award-winning exploration of this regional history exemplifies the Volunteer connection to community, illuminating the past to understand our world today.